I mentioned in an earlier post that I wrestled with whether to set my Oregon Trail novel in 1847 or 1848. I decided on 1847, because I wanted my characters to stop at the Whitman Mission. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, early pioneers to the Oregon Territory, were killed by Cayuse Indians in November 1847, so I had to have my wagon train reach their mission before that date.

My interest in the Whitman Mission began when I was a child growing up in Richland, Washington, just an hour’s drive from the site of the mission. My family took day trips to Walla Walla, Washington, to see the mission. The first diorama I ever saw was at the mission, depicting the events of the massacre.

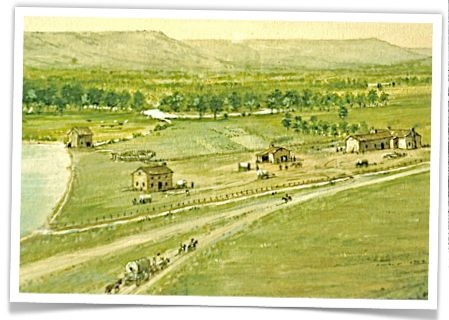

Whitman Mission was located in the Walla Walla River valley, surrounded by grassy meadows and rolling hills, just a few miles from where the Walla Walla flows into the Columbia River. The Whitmans established the mission in 1836. By the mid-1840s, they lived in a large white house. The mission also included adobe buildings where travelers could rest, a granary, a blacksmith shop, and a mill. The mission and its farms looked as well-established as many properties in the East.

The Whitman Mission was an important stop along the Oregon Trail. Shorter routes developed south of the mission, but if travelers needed food or medical assistance – and late in their journey, many were travel-worn – they went to the mission.

The mission was a last chance for emigrants to replenish supplies before their push over the Cascades to Oregon City. For the first time in months, they could eat white bread and butter, potatoes and vegetables.

Those who were bringing cattle to Oregon could leave their herds in Oregon for the winter and retrieve them the following spring. Many remained at the mission for a week or two while they built boats for the remainder of their journey down the Columbia.

Other emigrants spent the winter with the Whitmans before continuing to Oregon City. They worked on the Whitmans’ farmland in exchange for a place to stay.

In September 1847, Narcissa Whitman wrote of those staying at the mission in not very sympathetic terms:

Poor people—those that are not able to get on, or pay for what they need—are those that will most likely wish to stop here, judging from the past; and connected with this, is a disposition not to work, at any rate, not more than they can help.

As with all the forts and trading posts, the emigrants complained about the high costs of provisions. Their accounts of the journey show that they thought Marcus Whitman was as interested in commerce as in saving souls or treating disease.

For his part, Dr. Whitman believed that teaching the natives to farm was essential to their conversion to Christianity. Many of his letters survive, and one shows his interest in teaching the Cayuse to farm:

. . . although we bring the gospel as the first object we cannot gain an assurance unless they are attracted & retained by the plough & hoe, & in this way even before the language is acquired you may have the people drawn arround you & ready to hear your every instruction. And why should not this be our method of proceeding; Is it not what Paul meant when he said, “I become all things unto all men,” that he accommodated himself to the circumstances of the People? Why then should we not take the best, & may I not say, the only means to win them to Christ? Had I one doubt of the disposition of the Indians to cultivate I would not thus write; But having seen them for two season breaking ground with hoes & sticks & having given them the trial of the plough, I feel an entire confidence in their disposition & ability.

There were always tensions between the white and Indian populations, based on the changes that the Whitmans wanted the Cayuse to make in their way of life and on the increasing numbers of white emigrants to Oregon.

In November 1847, at the time of the massacre, there were 75 people at the mission. Of those, 52 were travelers passing through the mission. Others were orphaned children from wagon trains left for the Whitmans to raise.

One of the orphans, Catherine Sager Pringle, who was thirteen at the time of the massacre, later wrote a detailed account of daily life at the mission and of the massacre. See Across the Plains in 1844 (available on the PBS website for the series on The West). Catherine’s older brother John was one of those killed.

The massacre occurred after a measles epidemic swept through the Cayuse population. A wagon train of emigrants had brought measles to the mission in the autumn of 1847. The natives had no immunity. Half of the tribe died, while all but one white child recovered. The Indians blamed the Whitmans for the deaths of their people.

Mrs. Mary Saunders, whose husband Judge L.W. Saunders (a teacher at the mission school) died in the massacre, later described the situation:

Dr. Whitman treated the Indian children, but with very little success owing to the ignorance and superstition of their savage parents. They would take the medicine that he gave them, but at the same time, they still clung to their old remedy for all sickness, i.e., a sweating process followed by a plunge into cold water. The inevitable effect of such a treatment was …in almost every case… death. Altho Dr. Whitman explained to them the danger and warned them against it, his words were of no avail, and in their ignorance and superstition they blamed their kind friend for the death of their children and suspected him of trying to kill them off.

Of the 75 people at the mission, 14 were killed by the Indians. The Cayuse took many others captive. The residents of Oregon mounted a rescue campaign, but it took months to rescue the captives. Ultimately, five Cayuse men were hanged for the killings in June 1850.

For more on the Whitmans, see Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and the Opening of Old Oregon, by Clifford M. Drury (available on the National Park Service website for the Whitman Mission). Click here for the home page for the NPS website on the mission.

I love the history lessons I get from your postings.

Thanks, Sylvia!

Such a high price to pay!

This is interesting. I’d never read much history of the end of the Oregon Trail, rather the difficulties of the middle part, trying to reach Oregon. As a High Plains woman, I’d never even heard of a Cayuse tribe. Thanks for stretching my data bank!

Funny how our perspective changes based on our history.

I love the history lessons I get from your postings.

Thanks, Sylvia!

You grew up near Walla Walla? I spent a year in Spokane. In your research, you have drawn me into the history. I’m looking forward to reading your book.

Yes, I grew up in Richland, WA. And spent a lot of time in Idaho near Spokane (Coeur d’Alene).

Don and I were talking last night. I sighed remembering what a wonderful visit I had to Seattle in June. The weather was PERFECT. If it was like that 365, I’d have to consider moving there. 🙂

Such a high price to pay!

This is interesting. I’d never read much history of the end of the Oregon Trail, rather the difficulties of the middle part, trying to reach Oregon. As a High Plains woman, I’d never even heard of a Cayuse tribe. Thanks for stretching my data bank!

Funny how our perspective changes based on our history.

[…] Sager Pringle, mentioned in an earlier post, broke her leg while traveling the plains in 1844, when she was nine years old. She survived, but […]

You grew up near Walla Walla? I spent a year in Spokane. In your research, you have drawn me into the history. I’m looking forward to reading your book.

Yes, I grew up in Richland, WA. And spent a lot of time in Idaho near Spokane (Coeur d’Alene).

Don and I were talking last night. I sighed remembering what a wonderful visit I had to Seattle in June. The weather was PERFECT. If it was like that 365, I’d have to consider moving there. 🙂

[…] greater difficulty the Applegates faced came after they abandoned their wagons at the Whitman Mission, and built boats to float down the Columbia River. One of Jesse’s sons and one of his nephews, […]

[…] early emigrants to Oregon made Fort Nez Perce a stopping point. Many first rested at the Whitman Mission after it was established in 1836, then traveled the 20 miles along the Walla Walla River to Fort […]

[…] long, I forget which. I learned the basics—Lewis and Clark and Sacajawea, Fort Vancouver, the Whitman Mission, the importance of logging and railroads and salmon, Native American treaties made and broken and […]

[…] Sager Pringle, mentioned in an earlier post, broke her leg while traveling the plains in 1844, when she was nine years old. She survived, but […]

[…] greater difficulty the Applegates faced came after they abandoned their wagons at the Whitman Mission, and built boats to float down the Columbia River. One of Jesse’s sons and one of his nephews, […]

Have a mock trial for class having to do with this.

[…] early emigrants to Oregon made Fort Nez Perce a stopping point. Many first rested at the Whitman Mission after it was established in 1836, then traveled the 20 miles along the Walla Walla River to Fort […]

[…] have always been fascinated by the story of Narcissa Whitman, and it seems Rinker Buck was as well. Narcissa was the first white woman to cross the Rockies and […]

[…] long, I forget which. I learned the basics—Lewis and Clark and Sacajawea, Fort Vancouver, the Whitman Mission, the importance of logging and railroads and salmon, Native American treaties made and broken and […]

Have a mock trial for class having to do with this.

[…] have always been fascinated by the story of Narcissa Whitman, and it seems Rinker Buck was as well. Narcissa was the first white woman to cross the Rockies and […]

[…] leaving their homes and journeying west on the Oregon Trail. I’ve written about specific women—Narcissa Whitman, Jessie Benton Fremont, Elizabeth Dixon Smith, Keturah Belknap, and others—and quoted some of […]

[…] one day we drove to the Whitman Mission—the day trip of my childhood. My husband-to-be drove my parents’ Capri through rolling hills […]