By the middle of July, the Oregon emigrants in the 1840s hoped to have crossed the Continental Divide. Most of them crossed through South Pass.

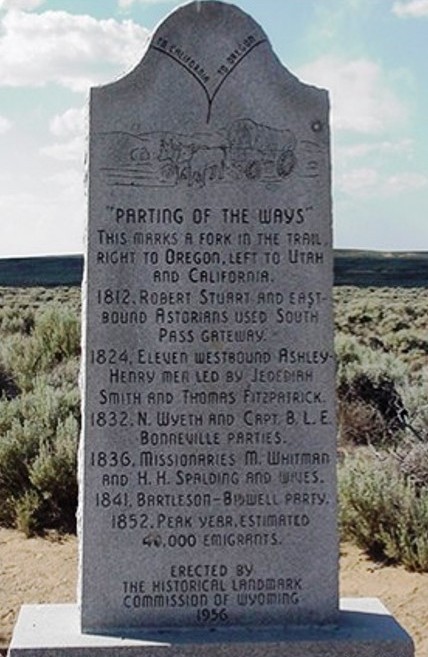

Native Americans had known of this route through the Rocky Mountains for centuries, but it was “discovered” by John Jacob Astor’s fur traders in 1812. South Pass made wagon travel through the Rockies to Oregon possible – the first wagons crossed the nation in 1832.

Bounded by the Wind River Range on one side and the Antelope Hills on the other, the sage-covered pass was so broad and the ascent so gentle that many travelers didn’t realize they had crossed the Continental Divide until they saw water flowing west at Pacific Springs. Those that did recognize the summit at South Pass wrote about how they had finally left home waters behind, or how they were finally approaching Oregon Territory. But even though they were technically in “Oregon Territory,” they still had months of difficult travel ahead.

A day or two after reaching South Pass, the emigrants had to decide whether to head due west on the Greenwood Cutoff (later called the Sublette Cutoff) or turn south toward Fort Bridger. Caleb Greenwood and Isaac Hitchcock explored the cutoff in 1844, but it did not become popular until the Gold Rush in 1849.

The point where the cutoff branched from the Fort Bridger trail was known as “the parting of the ways,” because often wagons that had traveled together for months separated at this point. The emigrants didn’t make their decisions based on where they were going (Oregon or California), but on the condition of their provisions and livestock.

Wagon companies in need of supplies or worried about their livestock’s health set out for Fort Bridger. Mormons headed to Salt Lake also took the Fort Bridger route.

But pioneers interested in speed took the cutoff. The Greenwood Cutoff saved seventy miles or more off the Fort Bridger route, but it meant fifty miles of desert between the Big Sandy River and the Green River.

The emigrants had to travel for twenty-four hours straight with no water. The travelers reached this part of the trail in the middle of summer. They set out on the cutoff at night, and got as far as they could before the hot sun rose.

Many animals died on the cutoff from thirst and fatigue. The teams that survived the journey stampeded when they finally scented the water at the Green River.

The emigrants thought this stretch of the trail was hard, but they had more travails ahead of them. The land from this point northwest through what is now Idaho was barren and dry. Even when they reached the great Snake River, they often traveled on rocky bluffs high above the river and couldn’t get to the water.

But then, the difficulties of travel through the desert and mountains made them appreciate the fertile Willamette Valley as the Promised Land when they finally got there.

Theresa,

Another great post! While not exactly in the same vein, I have to say that the Flint Hills in Kansas is some of the most beautiful countryside. I swear, I can still see the ruts made by wagon wheels from hundreds of years ago.

Thanks,

Linda Joyce

My husband has always enjoyed driving through the Flint Hills. For me, the wheat fields of Eastern Washington evoke the same feeling.

Thanks for your comment. Theresa

Such brave souls! We owe them a great debt of gratitude!

Indeed.

I’ll be driving right by that location in a few days. Expect to see breath-taking skies. Thanks for the research/background Theresa.

Travel safely.

[…] crossed the Sweetwater many times as the river meandered from just past Independence Rock toward South Pass. Actually, the river flowed the other way, but this is the direction in which the emigrants […]