The emigrants who traveled the Oregon Trail arrived in the Willamette Valley in late fall, or even after the first snowfall of winter. What did they do then? They were relieved the long journey was over, I’m sure, but how did they go about building a new life?

The emigrants who traveled the Oregon Trail arrived in the Willamette Valley in late fall, or even after the first snowfall of winter. What did they do then? They were relieved the long journey was over, I’m sure, but how did they go about building a new life?

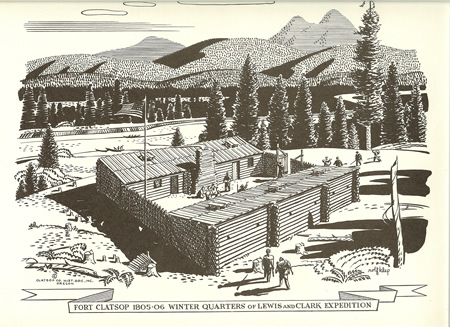

Beginning with Lewis and Clark, pioneers had trouble deciding how to spend their winters in the Pacific Northwest. My research told me that Lewis and Clark first stopped on the north side of the mouth of the Columbia River in November 1805. They called the site “Cape Disappointment,” which described their feelings at not finding the Northwest Passage they had sought.

They then moved to a site on the south side of the Columbia River and established a winter camp at Fort Clatsop, where they spent the winter of 1805-06. In the 106 days the Lewis and Clark expedition spent at Fort Clatsop, there were only twelve without rain and only six with sunshine. Imagine how depressing that must have been.

The emigrants on the Oregon Trail were no different in their struggle to find a comfortable place to spend the winter. When the 1840s emigrants reached Oregon, many of them relied on the charity of John McLaughlin, chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Vancouver. Later emigrants may have had family or friends waiting for them in Oregon. Some travelers found primitive homes or tents that already existed in the area.

For example, in 1843, Jesse Applegate’s family spent their first winter at the old Methodist mission upriver from where Oregon City would be founded. They went hungry during the cold, wet winter—so hungry that a begging Indian gave his dried venison to the Applegate children, instead of taking their food. Yet a year later, Jesse Applegate was the sixth wealthiest man in Oregon, according to the tax rolls, due largely to the value of his cattle, so he had some early success in Oregon

As another example, Elizabeth Dixon Smith Geer found a small shed in Portland in which to spend the winter of 1847-48. She describes it as “a small, leaky concern with two families already in it.” She made a pallet on the mud floor for her sick husband, and he stayed in the shed until he died several weeks later.

Later, she writes a friend,

If I could tell you how we suffer you would not believe it. Our house, or rather a shed joined to a house, leaks all over. The roof descends in such a manner that the rain runs right down into the fire.

The shed was

constructed by setting up studs five feet high on the lowest side. The other side joins the cabin. It is boarded up with clapboards and several of them are torn off in places, and there is no shutter to our door; but if it was not for the rain putting out the fire and leaking all over the house we would be comfortable.

The more intrepid pioneers sought out their new homes immediately and filed homesteader’s claims. In 1847, when my novel about the Oregon Trail takes place, every male who was 21 or older could claim 640 acres of land (one square mile). Within six months of filing a claim for the land, he had to make improvements in the form of a building or fences, and he had to take up residence on the land. If he didn’t, there were provisions for paying taxes instead.

I haven’t been able to find accounts of how the travelers decided on their sites, so I’ve had to use my imagination in picking out land for them. I assume they wanted running water, fairly flat land they could clear and farm. I picture these emigrants, most of them bedraggled and penniless, searching for a spot to call home.

And I add to that picture my own memories of winters in Oregon. I lived in the Willamette Valley (Corvallis, OR) when I was a preschooler. Those winters of 1959 and 1960 aren’t my earliest memories of winter, but I remember them. Weeks of constant grey and rain, when I was forced to stay inside through recess, and I was bored with only my younger brother as playmate.

So those memories color my depiction of the emigrants’ winters in Oregon, and I can easily understand how depressing Lewis and Clark and their companions must have found it to have only six days of sunshine all winter.

To create the winter scenes in my novels, then, I combined my research, my imagination, and my memories. Is it truth? Who knows? When I get the books published, you can judge.

How do you picture the early pioneers wintering in Oregon? Writers, how do you combine research, imagination, and memory?

I follow the thin thread of research and make it the backbone, then add muscles of imagination, and cover it with the skin of memory. After careful edits and many critiques, life-like characters emerge.

Sally, you used much more imagery than I can in your description.

Theresa

One of the things I did was drive out to Jewell County Kansas so I could see the land and understand what it was that made people stop at that particular place. In other words, since you know the Willamette Valley, (or can get photos of it) I wonder if you can imagine why someone would live in one particular place or another. For example, the Quakers all settled along a river in northern Jewell County and their settlements were on the flatter land. It’s beautiful country out there. I can see why they stopped.

Janet,

I’ve been using Google maps to do what you suggest. The land has changed so much, but I figure the basic contours and watersheds are similar.

Theresa