When autumn came to 1848, San Francisco was already a boom town and coping with the influx of gold. At the same time, rumors of the gold rush were just reaching Washington, D.C.

By late September, more than 6000 men were mining in California. Wealth from the gold fields flooded into San Francisco soon after nuggets were discovered at Sutter’s Mill early in the year.

Gold dust became the most frequent means of exchange in the town. So much gold dust was bartered that its value decreased. Men who had slaved to find it grew despondent that their labor brought them little in return.

In one letter to the editor of the Californian newspaper, a writer asked:

How long is gold to remain at the extremely low value which it now maintains? This is an inquiry which is not only propounded to us daily but presents itself in the forms of many debilitated holders of this pure material — men who have wasted their strength and lost their health in obtaining this commodity, so valuable abroad, but now of so little value here.

As a result, business leaders including Samuel Brannan met and set the price of gold at $16 per ounce. In addition, they petitioned Congress to establish a mint in San Francisco. They argued,

Unless . . . prompt measures are taken to establish a Branch Mint in California, . . . the greatest portion of the gold taken from American soil on the Pacific will be coined in foreign countries. . . . Oregon and California are left almost entirely without a circulating medium for the transaction of business, and . . . United States coin may be said to be nearly unknown in these Territories. Trade is greatly embarrassed in consequence, and the scarcity of coin and the abundance of gold dust has already caused the latter to be sold at about one half its intrinsic value.

Despite these measures to stabilize commerce in the West, many of the early miners—the forty-eighters—were already beginning to pack it in. Contrary to news reports, nuggets did not lie on the ground waiting to be found. Mining was too hard and their health suffered. Summer heat and illness caused many miners to abandon their search for riches.

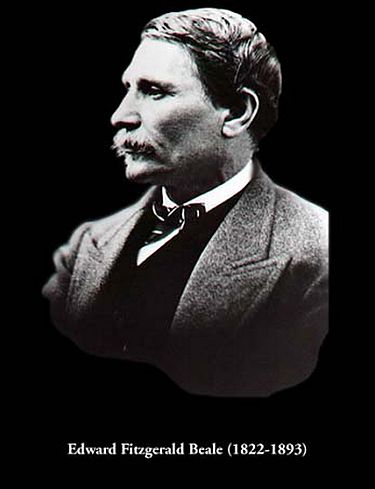

Meanwhile, plausible reports of the gold find were reaching the East Coast in September of that year. In mid-September, the New Orleans Daily Picayune published an interview with Lt. Edward Beale who was bringing samples of gold from California to Washington, D.C. Beale reached Washington on September 18, but his reports were received skeptically.

Nevertheless, some of the rumors of gold caused a furor. On September 21, the New York Herald reported:

All Washington is in a ferment with the news of the immense bed of gold, which, it is said, has been discovered in California. Nothing else is talked about. Democrats, Whigs, free soil men, hunkers, barnburners, abolitionists, all, all are engrossed by the wonderful intelligence. The real El Dorado has at length been discovered, and hereafter let not cynics doubt that such a place exists.

So despite initial skepticism at the reports that gold had been found, the East soon developed gold fever. At the same time, the locals in California were already worrying about the impact of the discovery on their community.

When have you seen current events interpreted differently in different regions?

Hi, I saw you referenced one of my pieces in your article, just wanted to let you know that the address has slightly changed, as I’ve shifted domains. The article address is now, http://fernhilltoursdotcom.wordpress.com/2014/07/25/got-a-revolution-the-beginning-of-the-california-gold-rush-1848/

Best, FHT

Thanks for letting me know. I’ve updated the link in the post.

Theresa

[…] once news of the discovery of gold in California reached the East Coast, the pattern of emigration to the West changed forever. The preferred location shifted immediately […]