I wrote a couple of months ago about how the Manhattan Project preserved the natural beauty of the Columbia Reach in eastern Washington. In addition to preserving this unique part of our nation’s landscape, the Manhattan Project also enhanced the development of my home town of Richland, Washington.

2015 is the 70th anniversary of the dropping of the two atomic bombs on Japan. These bombs were the result of work done in secret at Hanford and elsewhere. Numerous media articles this month have discussed the impact of nuclear bombs on Japan and on the U.S. Army. But work on the atomic bomb impacted civilian populations in the U.S. as well—at least there was a significant impact on my home community.

In January 1943, the Army selected the town of Hanford, Washington, as the site for plutonium production on the Manhattan Project. The criteria for the selection focused on the isolation of the area and the ready availability of water and electricity. The desert of Eastern Washington provided the isolation. The Columbia River that flowed through that desert and the hydroelectric dams on the river provided the necessary water and electricity.

Beginning in February 1943, the Army acquired vast amounts of land under the Second War Powers Act. The three hundred residents of Hanford were relocated, and the land became the Hanford Engineering Works.

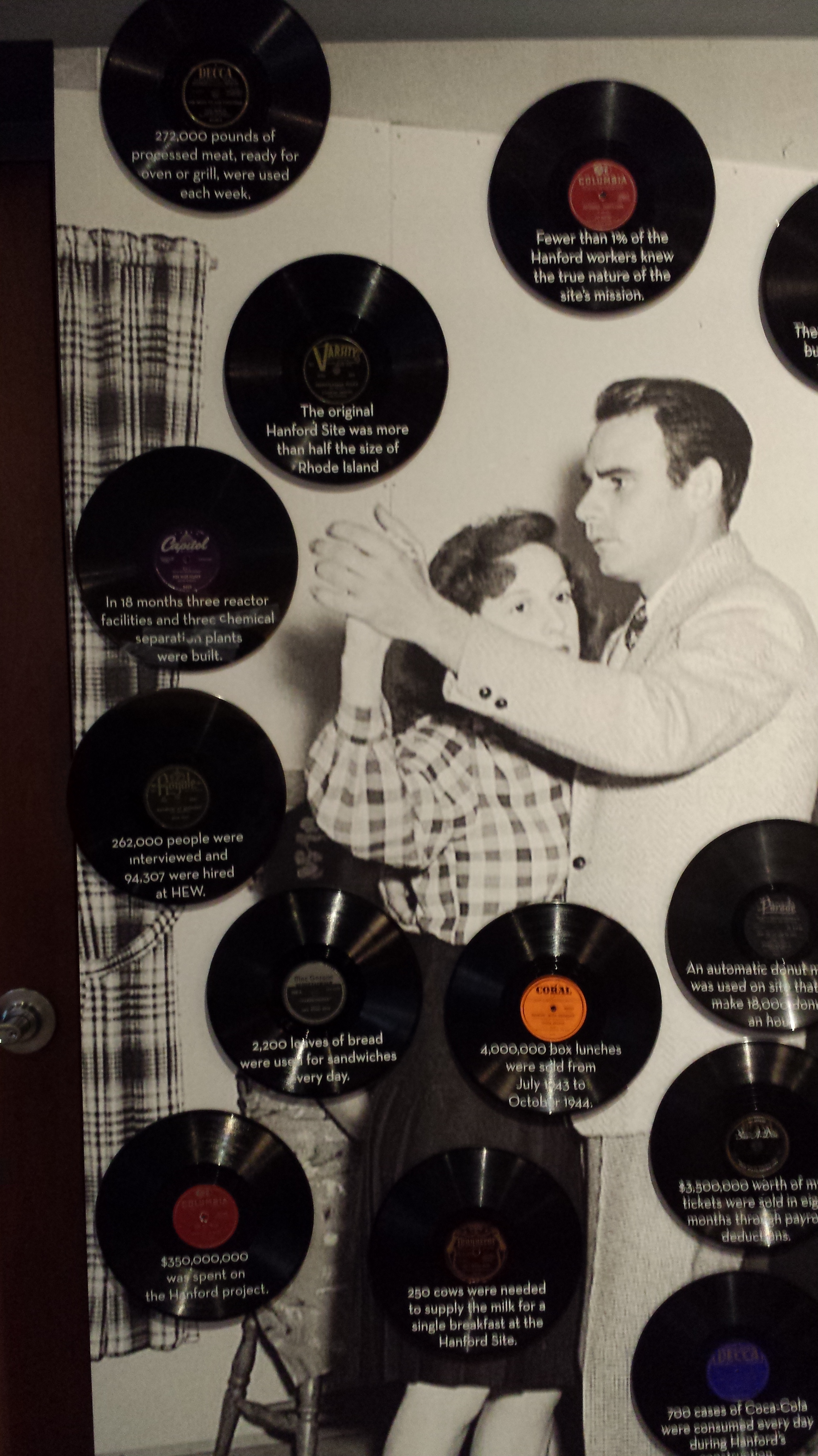

The Hanford Engineering Works started as a tent camp, then barracks were built, and then the amenities of a town, including the largest general delivery post office anywhere in the world. By 1944, over 50,000 people lived at Hanford. It was the fourth largest city in Washington State and the largest voting precinct anywhere in the United States that year.

And it had been built from nothing in less than two years

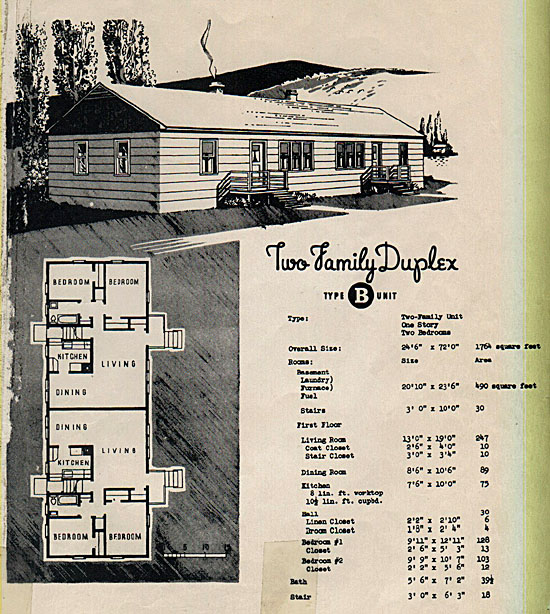

The nearby town of Richland was incorporated in 1910, but it remained a small backwater until 1943. That year, Richland was tapped to replace the Army barracks and to become the bedroom community for Hanford. The Army hired Gus Pehrson, a noted Spokane architect, to construct a town for 5,700 people (later increased to 16,000). The town needed houses, utilities, retail, services—anything and everything. Pehrson had 75 days to do it. But it only needed to last for five years.

Pehrson’s buildings lasted for far more than five years. In the late 1950s, my family lived in a duplex designed and built by Pehrson. In 2015—seventy-two years later—many of Pehrson’s houses are still occupied.

Richland, which had had only 300 people in the summer of 1943, boasted 25,000 by August 1945. After the war, in 1946, the Hanford residential camp was demolished, but the town of Richland continued to grow. Its fortunes ebbed and flowed first with the development of nuclear power and weapons (and the research to support both), and then with the clean-up of the Hanford area.

Without the Manhattan Project, Richland would be a very different community than it is today, and I would be a different person than I am. The nuclear industry provided my father a long and successful career. Pehrson’s design provided my family with the first home I remember. I was told that Richland had the highest per capita percentage of Ph.D. engineers of any town in the world—and many of those engineers’ well-educated wives were my teachers.

Richland is my home town, and I probably would think of it fondly no matter what. Still, it was a better place to grow up than it could have been, because of the Manhattan Project.

How has a world event affected your life? Was the impact for better or for worse?