The last survivor of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake died earlier this month. William Del Monte was three months old when the earthquake struck and 109 when he died on January 11. Reading the news articles about his life and death brought to mind all the novels I’ve read about the earthquake and the fires that followed.

I learned a lot about history through reading historical fiction. One of my favorite authors from childhood into my young adulthood was Phyllis Whitney. She wrote at least two novels about San Francisco during 1906—The Fire and the Gold and The Trembling Hills. The saga of the beautiful city crumbling into rubble, followed by days of burning buildings fascinated me, both as a child and as an adult.

I first visited San Francisco when I was about ten, though I’d been to the airport earlier on trips to visit my grandparents. San Francisco always seemed not only beautiful but exotic—Chinatown, Fisherman’s Wharf, and cable cars—all attractions that didn’t exist in my small town life. On one of his business trips, my father bought me a Chinese outfit (black trousers and brocade shirt that buttoned with frogs) which I wore for Halloween for a couple of years.

I’ve visited San Francisco several times as an adult, but my early impressions of the city came back to me when I began researching my current work-in-progress, part of which takes place in California during the Gold Rush years. In my research, I learned that the fire after the 1906 earthquake was far from the first conflagration in San Francisco’s history.

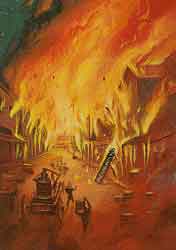

Frequent fires shaped the development of both San Francisco and Sacramento, and the years of 1849 to 1851 were a particularly fiery time in the history of both towns. My novel takes place between 1848 and 1850. Sacramento is one of the primary settings of the novel, and some scenes are set in San Francisco as well. So I decided learning something about the San Francisco and Sacramento fires would be good background. This post focuses on San Francisco.

The First Great Fire of San Francisco occurred on Christmas Eve, December 24, 1849. The fire started at Dennison’s Exchange on Kearny Street between Clay and Jackson Streets. The Exchange was a three-storied building used as a saloon and gambling hall. Allegedly, a black man started the fire after a white Southern bartender beat him when he ordered a drink. The fire spread rapidly and destroyed over fifty buildings (most of the city at that time), causing $1,500,000 damage.

Within days of the First Great Fire, the city organized a variety of fire companies, and in less than a month, San Francisco rebuilt. The hasty reconstruction shows what a boom town San Francisco was—plenty of labor and plenty of money to throw up buildings to generate profits from the Forty-Niners flooding into California.

Less than five months later, on May 4, 1850, a Second Great Fire broke out. This one started in the United States Exchange, another saloon and gambling house, built on the same site as Dennison’s Exchange. This time, paroled Australian convicts were blamed for the fire. This fire burned 300 buildings and caused $4,000,000 damage. By this time, the city had a fledging police department that controlled looting, but the fire department was still inadequate to the task.

A week after the Second Great Fire, construction began on the city’s first brick building, and more fire companies were started. But just a few weeks after the second fire, on June 14, 1850, the Third Great Fire occurred. This fire began in the Sacramento Bakery in the Merchants Hotel at Clay and Kearny Streets, probably because of a faulty chimney. It destroyed 300 more buildings, with damages estimated at $5,000,000.

More fire companies resulted, staffed by experienced firemen from the East. But on September 17, 1850 the Fourth Great Fire destroyed 150 buildings with losses of $500,000.

Although these four fires were called the Great Fires, 1850 saw other conflagrations also. In late October 1850 the City Hospital burned, though the 150 patients were saved. Loss was $40,000. And in mid-December 1850 a fire started in the Cooke Bros. and Co. Building, causing damage of $100,000.

Then on May 3, 1851, a fire began in a paint shop. The fire consumed wood buildings, then reached a three-story brick store. The citizenry thought the brick building would hold, but it did not. Over 1500 houses were destroyed, many people died, and the losses were $12,000,000.

Another fire in June 1851 destroyed many wood and adobe landmarks of Old San Francisco, and cost another $3,000,000 in damage.

Each time, the city rebuilt. The boomtown could do no less. If the original landowners would not build, squatters would take their place.

Fifty-five years later, when the 1906 earthquake and fires hit San Francisco, some residents of the city would have remembered these conflagrations from 1849-51. So we are just two lifetimes away from these great early fires—from the witnesses of the original fires to William Del Monte to 2016 it has been 167 years, but just two lifetimes.

Thinking of these great disasters reminds us how short modern history is. We are just two lifetimes removed from the Gold Rush.

We usually do not remember the role that fire has played in creating our modern cities. Fires and earthquakes and floods and mudslides can overcome all our human ingenuity and productivity in an instant. It takes far less time to destroy a city than two lifetimes.

And still we rebuild.

When has a natural disaster impacted you?

I love this period of history! We have a screenplay that takes place in a fictional coastal town with an adobe mission, and it did place in the quarterfinalist category of a competition! Still unproduced. The visuals you have here are stunning. I am fond of Mark Twain’s reminiscences of the earthquake of 1906, and as I recall (haven’t read them for a long time) they capture the tragedy but also some of the humor that occurred around him. Best to you for the completion of your project. Sounds fascinating!

Thanks for the comment. And good luck with your screenplay also.

Theresa